Here, I want to focus on how companies can create Docker images in a way that takes full advantage of how Docker layers are constructed and how they’re stored on disk.

Many companies that use Docker follow one of two strategies: either each team is fully responsible for creating and maintaining its own images, or there’s a dedicated team that curates base images — adding essential security and logging dependencies — before development teams build on top of them.

When development teams start working on their own Docker images, whether they’re building from official language base images or from a DevOps‑maintained base image, they typically still have the freedom to choose which framework to use for each service.

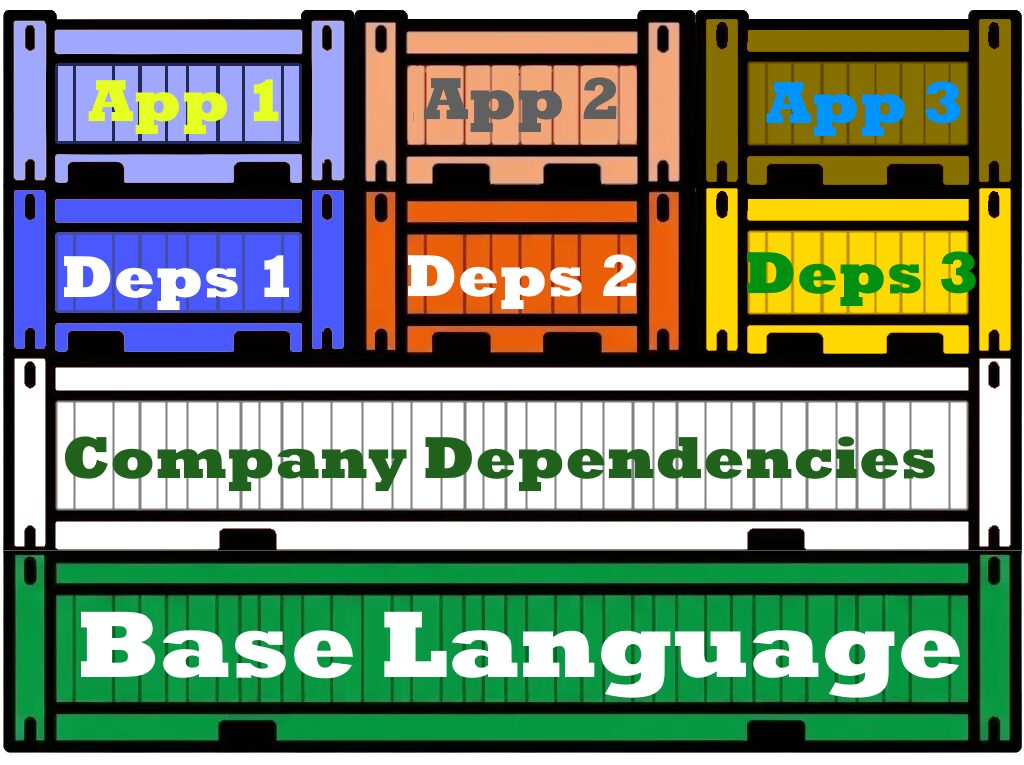

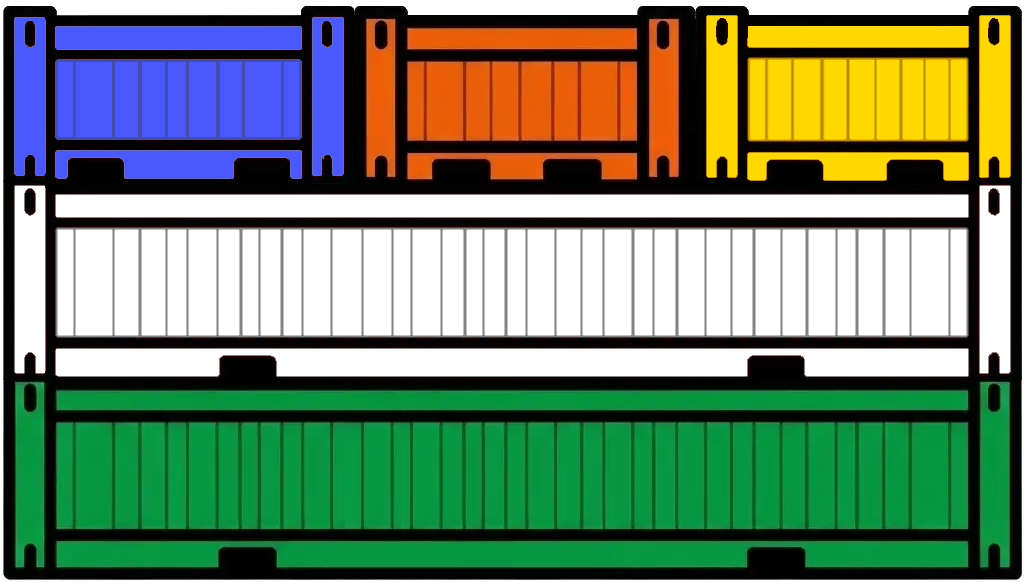

In most cases, a team’s services share the same frameworks and dependencies, with only a few exceptions. This means any given service will have 90% or more of its dependencies in common with the others that team manages — so the typical stack looks like this:

Given how Docker layers are created, even a slightly different dependency list between two images is enough to generate a different hash during the dependency installation step. As a result, even if they’re built on the same machine with caching enabled, Docker will create separate layers — meaning no space is saved on the filesystem and no time is saved during the build.

In the same way, the company’s base image — on top of the language‑specific installation — can include security‑related dependencies as well as common frameworks and libraries (Rails, React, Hibernate, Django, etc.). Here’s an example in Ruby: the application is built on top of a company‑wide base image that already includes essential security configurations.

# Dockerfile for base company ruby image

FROM ruby:3.3.1

# Add user and any needed secure dependencies

RUN useradd -u 1000 app; \

mkdir -p /home/app/project; \

chown app.app -R /home/app; \

echo "INSTALLING SECURITY DEPENDENCIES"

# User the application user and work on contained project folder

USER app

WORKDIR /home/app/project# Dockerfile for application

# Built from company global ruby image

FROM base

# Add dependencies file

COPY --chown=app:app app_source/Gemfile /home/app/project/

# Install dependencies

RUN bundle installHere, the image has only a few dependencies: two are common across services — the Rails framework and Sidekiq — while the last one, Zyra, is specific to this application.

# frozen_string_literal: true

# Gemfile for the application

source 'https://rubygems.org'

ruby '3.3.1'

gem 'rails', '~> 7.2.x'

gem 'sidekiq', '~> 7.0'

gem 'zyra', '1.2.0'Now, most of the applications the team handle will use Rails and Sidekiq so we can extract those to a common base image and then we can start looking at what will be saved.

# Dockerfile for application

# Built from company global ruby image

FROM base

# Add common dependencies file

COPY --chown=app:app framework_source/Gemfile /home/app/project/

# Install dependencies

RUN bundle install# frozen_string_literal: true

# Gemfile for base common framework image

source 'https://rubygems.org'

ruby '3.3.1'

gem 'rails', '~> 7.2.x'

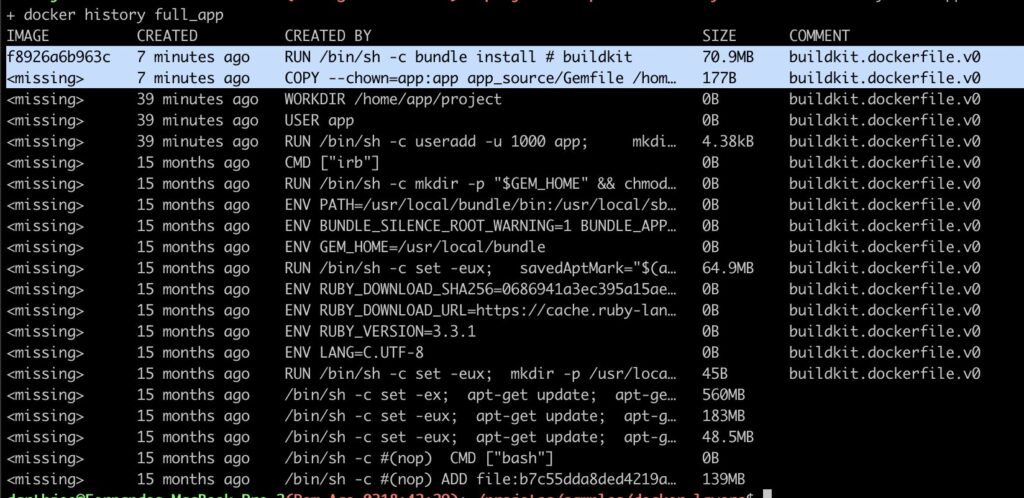

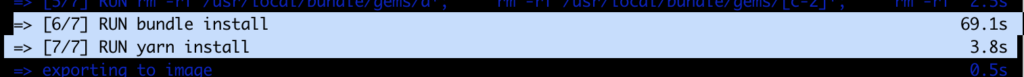

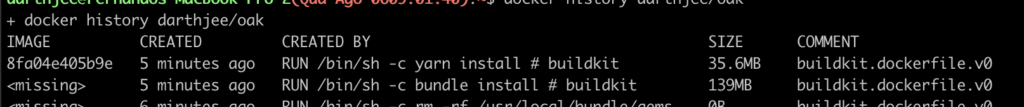

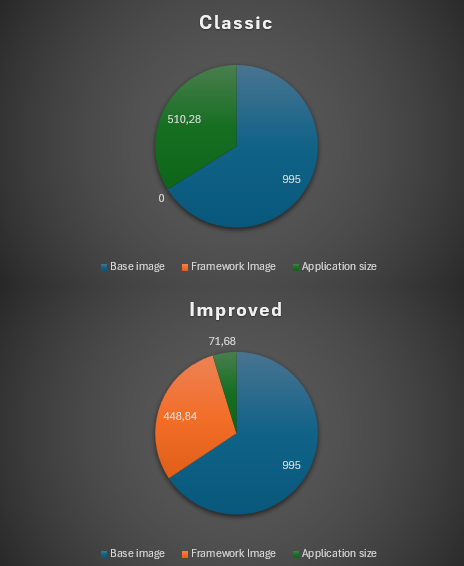

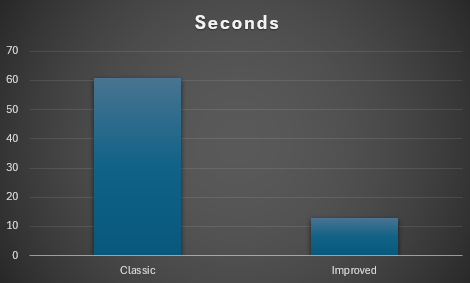

gem 'sidekiq', '~> 7.0'In a regular build, all dependencies are installed during image creation, which means extra build time and a separate dependency layer stored for each service. In this example, that layer is only 70 MB, but it could easily reach 200 MB and take more than a minute to be completed … just for that step alone.

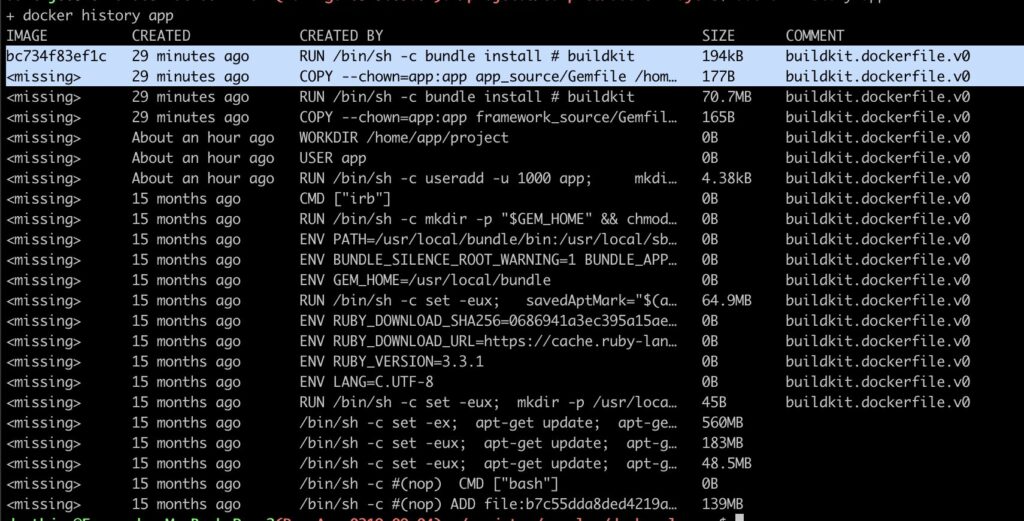

Now, when we examine the image built using a common base framework, we observe that the installation of the final, application-specific dependency takes only a fraction of the time and resources compared to the framework-related dependencies. Consequently, the build process is significantly faster, often completing in less than 10% of the original build time.

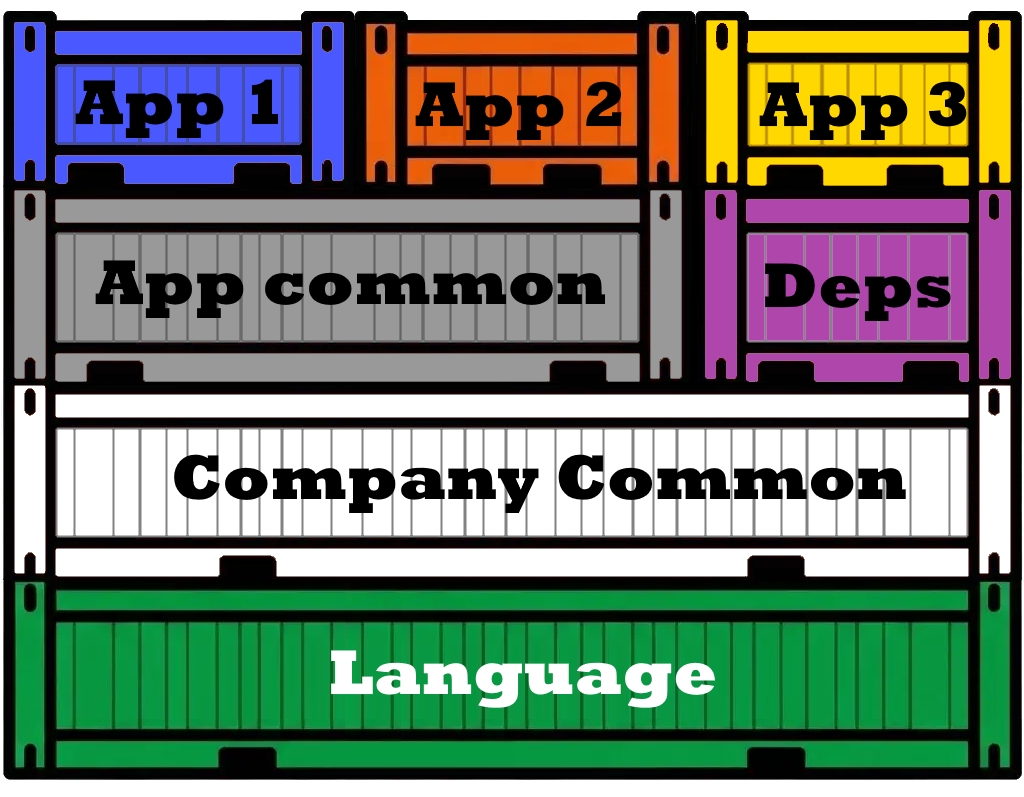

Under this approach, a company’s Docker images would follow a clear layered hierarchy: a foundational company base image (containing default security dependencies), followed by a framework-specific image built upon it, and finally, the application’s distinct layers. Importantly, this architecture retains the flexibility for teams to develop using alternative frameworks, allowing them to opt out of utilizing this particular framework base image.

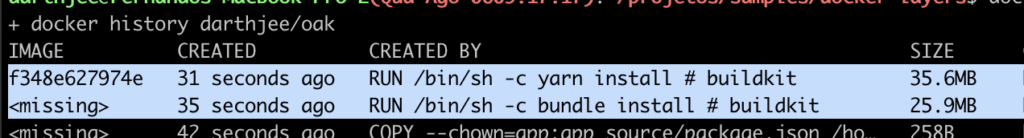

Lets looks at a real example of a small project where dependencies took a lot of time and space

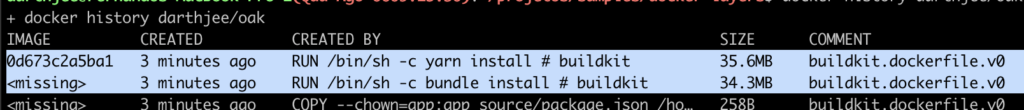

Compared with the build having a common base image common across the company where common dependencies have been installed, we can see a big save in space and time (not space-time 😉 )

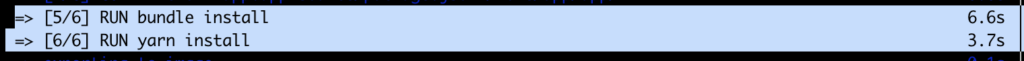

Another strategy would be to have yet another layer where each project also has a base image containing all the dependencies, just not the application code, this saves a little bit less, mostly time but not so much space as it would depend on how many versions of the application are stored

We can see here that there is a drastic reduction in the application layer size and the time it takes to build the image

With this, we can save:

- Space when storing all applications images

- CI time when testing

- Developer time as well

- CI time when deploying as deployment only transfer new layers

- Developer time as well

- Faster hot fixes deployment as well

- Developer time when performing image upgrades

Leave a Reply